AI: A challenge or opportunity for writing (or both)

As we consider what generative artificial intelligence (AI) means for education, we might experience a plethora of emotions: anxiety, fear, excitement and curiosity. Regardless of how we feel, this technology is here, and we must respond accordingly. As technology evolves, so too must our approach to teaching and writing. The advent of generative AI presents challenges and opportunities for educators and students, especially when it comes to the use of writing assignments in the classroom.

Generative AI tools, such as Gemini or ChatGPT, could revolutionize how we approach writing if they have not already done so. They can assist in drafting, brainstorming and refining text. However, this also raises concerns about creativity, critical thinking and academic integrity. As you contemplate how to best respond to this technology, the key is to view AI as a resource that, when used responsibly, can enhance the writing process rather than undermine it.

Why do we use writing assignments?

Writing assignments are a familiar and longstanding form of assessment, but they are also much more. Well-designed writing assignments can help students develop critical thinking, communication skills and a deep understanding of subject matter. They encourage students to organize their thoughts, argue points logically and engage with content creatively. Despite the rise of AI, we still want our students to engage in these practices that writing has supported for so long.

Thus, you might wonder: How can we ensure that writing assignments are still effective in the age of AI? The research on teaching writing has already prepared us for this moment. With some research-based best practices, we can continue to integrate and use these assessments into our instruction, although we may need to reconsider and reinvigorate our practices and approaches.

Best practices for teaching writing for this moment

Instead of solely evaluating final products, emphasize the writing process (Barnett, 1989; Elbow, 1998): brainstorming, drafting and revising. Engaging with and evaluating the work of students while they are on the journey and not just after they have reached the destination is critical (Atwell, 2014). By accompanying and supporting students throughout the writing process, you demonstrate your commitment to their success, can more effectively monitor their progress and more regularly and substantively interact with students. With thoughtful and strategic integration, AI can help students at each step, fostering a deeper engagement with their work without supplanting their own responsibility and agency.

Prompting is writing. As students develop prompts, they must think rhetorically (Bitzer, 1968): What should the output do (purpose), who does it address (audience), and what format should the output use (genre)? Teach students to consider the rhetorical situation — purpose, audience and genre — when writing and using AI tools.

By understanding how to craft effective prompts, students enhance their communication skills and learn to use AI as a tool for clarity and precision. Various prompt engineering strategies, such as RTFC (role, task, format and constraints), summon students to think rhetorically.

Incorporate real-world tasks into writing assignments. Authentic assessments will impress upon students the value of their learning. There are a few additional ways to create more meaningful and relevant assessments for students:

- Primary research: Students could conduct field research: For example, you could encourage students to complete observations, surveys or interviews. Gathering their own data will invite students to take more ownership of their discussion and findings.

- Multimodal composition: In addition, you might consider challenging students to step beyond the familiar essay and to instead write in genres that resemble what they will do and use in the “real world.” This could include multimodal composition, with students using various formats such as podcasts, infographics, videos or social media. One powerful assessment that invites students to use a cornucopia of “real world” genres is the multi-genre research paper (Langstraat, n.d.; Romano, 2000). A multigenre research paper offers students multiple means of engagement and expression, one way of implementing Universal Design for Learning.

Whether you integrate primary research or use multimodal composition, students will appreciate the more hands-on and tangible experience they will have. These activities help students apply and communicate their learning in practical contexts, preparing them for real-life challenges.

Reflection is a critical component of learning. Reflection provides students the opportunity and space to look back, look around and look ahead, thus coming to take ownership of their learning and engage in more metacognition (Chang, 2019), or thinking about how they think and learn.

Please provide opportunities for students to reflect on their writing processes; the role of others and other resources, including AI, in their work; and what they have learned. Students can journal or record media reflecting on their experiences. This mindfulness helps students become more aware of their skills and areas for growth.

Writing should not take place alone and in isolation; collaboration and interaction are powerful for improving both the process and the final product. Students can encounter and consider ideas and feedback from various resources, all of which they synthesize and curate to create compelling writing.

Please encourage collaboration among students and the use of resources such as peer feedback, writing centers and AI tools. Viewing writing as a social process can lead to richer, more diverse outcomes and a stronger sense of community.

The future of writing in the age of AI

A hybrid and cyborg process

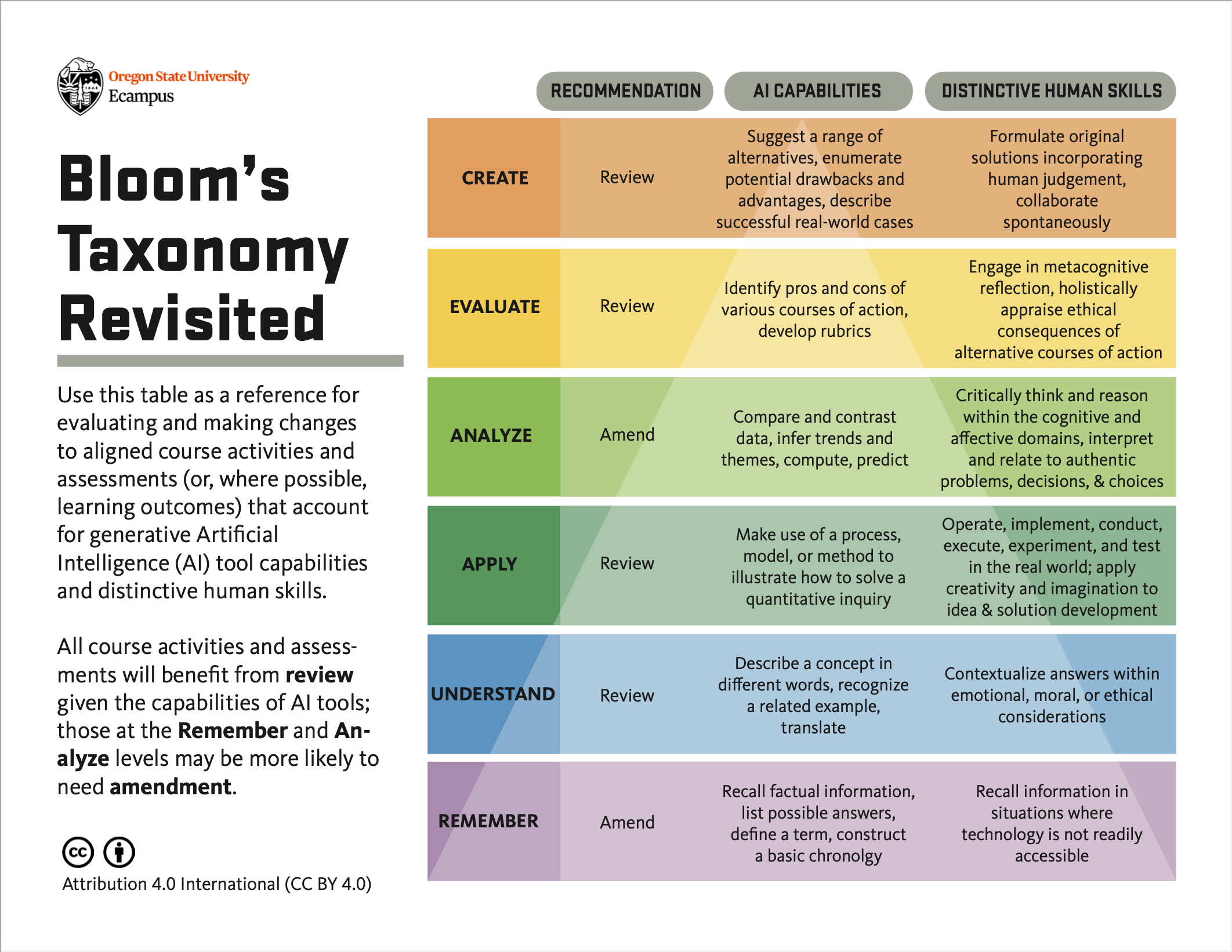

Ultimately, the future of writing could rest in a hybrid, or cyborg, approach where humans and AI collaborate. This writing "cyborg" (Haraway, 2000) combines human creativity and critical thinking with AI's efficiency and data handling capabilities. Students can continue to engage in critical thinking on Bloom’s Taxonomy as they use generative AI (Oregon State University Ecampus, n.d.). Educators should prepare students for this future by teaching them to use AI tools effectively and ethically.

Writing, prompting, examining and curating to learn

You might have encountered the phrase “writing to learn.” In the age of AI, students will continue to write to learn, but perhaps not in the same manner. The role of writing is expanding. Students will not only write to demonstrate their learning but also to engage in prompting AI, examining AI-generated content, and curating information. This shift requires a new set of skills, including critical evaluation of AI outputs and ethical considerations in using AI-generated content.

Conclusion

The integration of generative AI in writing education is inevitable. By focusing on process, rhetorical awareness, authentic tasks, reflection, and collaboration, educators can harness the potential of AI to enhance learning outcomes. The future of writing is a blend of human ingenuity and AI assistance, creating a more dynamic educational experience.

By embracing these changes, we can prepare students not just to survive but to thrive in a world where AI and human creativity will work hand in hand.

Related resources

Presentations

Other resources

Active and alternative assessments

Setting expectations for academic integrity

Regular and substantive interaction

Developing a plan for feedback

Bloom’s taxonomy revisited for the age of AI (Oregon State University)

References

Atwell, N. (2014). In the middle: A lifetime of learning about writing, reading, and adolescents. Hienemann.

Barnett, M.A. (1989). Writing as a process. The French Review, 63(1), 31-44.

Bitzer, L.F. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric (1), 1-14.

Chang, B. (2019). Reflection in learning. Online Learning Journal, 23(1), 95-110.

Elbow, P. (1998). Writing with power: Techniques for mastering the writing process (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Haraway, D.J., (2000). The cyborg manifesto. In D. Bell and B.M. Kennedy (Eds.), The cybercultures reader (pp. 291-324). Routledge.

Langstraat, L. (n.d.). Multigenre: An introduction. Writing@CSU. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

Oregon State University ECampus. (n.d.). Bloom’s Taxonomy revisited. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

Romano, T. (2000). Blending genres, altering style: Writing multigenre papers. Hienemann.

Created on August 27, 2024